Imagine the eighteen months of General Motors CEO Mary Barra’s life. In her short tenure, GM will have recalled more than 30 million automobiles worldwide. Her firm is besieged by allegations of a caustic culture of carelessness, dysfunctional bureaucracy, warped communication channels, sloppy manufacturing supervision, and even an attempt to cover-up whatever wrong-doing led to persistent installation of faulty ignition switches.

Barra may not have created these problems, but she did inherit them. And she lives with them. Surely they crowd her every thought and dictate her every action. Nothing can cross her mind that isn’t filtered through these indignities. Every move has to be carefully calculated in light of them. Barra is surely in a spotlight where everything she thinks and does matters. Big time.

Barra’s intellectual and behavioral states are forcibly affected by this crisis. Rightly so. But image her emotional state. Her body is dumping cortisol and epinephrine at an astonishing rate. Both of these neuro-chemicals cause a host of physical and cognitive ailments as well as hyper-tension and depression. The longer the body is exposed to the chemicals, the greater their short- and long-term toll.

Mary Barra is a shuddering study in stress.

Stress is a bit of a double-edge sword. It can be a positive force in focusing attention, energizing action, and boosting determination. It can help us buckle down and hold fast. It encourages clear-headed prioritization, swift and unified response, and the resolve to carry it through. Often stress rallies our resources. Well-managed, it’s a powerful performance multiplier.

But the other side of stress’s sword is sharp and it cuts deep. What once lifted us can now hobble us. The question is when and why this happens, and what to do about it.

This past June a study published in the Journal of Neuroscience suggests that a neural “switch” determines the difference between perseverance and breakdown in the face of stressful events. The researchers found that inducing activity in the medial prefrontal cortex—the part of the brain that processes emotions—of laboratory rats left previously steadfast experimental subjects deflated. Our furry friends went from fighting the brave fight to surrendering.

Surely it’s a long way from rats to executives (well, maybe not in some cases), but the “switch” idea neatly explicates the long documented phenomenon known as learned helplessness. Learned helplessness is triggered when people are confronted with negative consequences that they cannot control. When barraged with no recourse, we tend to give up. We learn to be helpless in the face of a punishing, uncontrollable environment.

The “switch” study may explain why the breakdown occurs, but what’s more important is what we can do about it. How can we counter the corrosive effects of stress? What coping mechanisms are available?

I call these coping mechanisms sources of renewal. Over the last three years I’ve conducted in-depth interviews with 127 executives from 18 different countries—all at the senior vice-president or equivalent rank—to uncover exactly what executives the world-over do to renew their selves in the face of relentless tension. Lots of research tells us that there are remedies, but little reveals the real practices of busy professionals.

After providing a thorough description of stress and what is known about it, I described what the concept of renewal as anything that emotionally removes one from perseverating on, and relieves the symptoms of, stressful events (no examples were provided as soliciting their specific practices was the purpose of the study). I then explained that the deleterious effects of stress can, at least partially, be counteracted by spending 20 to 30 minutes per day engaging in renewal activities.

The first question I asked was if they were aware of that. Thirty-six percent answered some variety of “yes”, 40% “vaguely”, and 24% “no”. The obvious follow-up was: “How many days a week do you spend 20-30 minutes in renewal-like activities?” Eighteen percent said four or more, 42% said three or two, and 40% reported they engaged in such activities once, or less than once, a week.

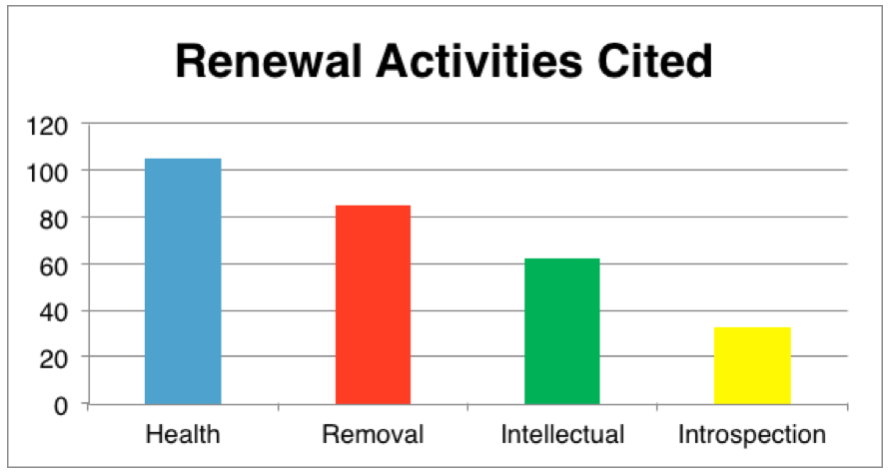

The next question was the heart of the study: What, exactly, do you do to “renew” yourself? Answers ranged far and wide. It was necessary to code them into categories. As the table below illustrates, four representative categories were created: Health, Removal, Intellectual, and Introspective. Two-hundred and eighty five responses are represented here.

Health—some form of exercise, of outright exertion of muscular tissue, as well as sleep and diet—was the most common. It included things like running, hiking, yoga, weight-lifting, any number of sports such as baseball or soccer, balanced caloric intake, and a good eight hours repose. These may be called merely maintenance, but they critical nonetheless. Study after study demonstrates that tending to health helps to purge the body of stress’s toxic waste.

Second was Removal. Some would call this “escapism,” which it is, though that term doesn’t sit well. I thought of Removal as anything that whisks one way from work’s every day struggles. Attending concerts or plays or theater, watching television, going to the movies or theater or sporting events, fine dining, and the like, were cited. Interestingly, stopping by the spa or the tavern was also mentioned. Family time fit here too. Removal carries one someplace other than where one works every day.

The third, Intellectual, contained puzzles, games like chess or Scrabble (Dungeons and Dragons was mentioned three times!), studying history or botany, bird-watching, hobbies like model building, and voracious reading. These activities immerse one in mind-challenging activities. Intellectual engages us as well as calms us.

The fourth and final category was Introspection. Transcendental meditation, prayer, breathing techniques, setting aside time for reflection, therapy (including Neural Feedback Training), and participating in support groups were among renewal activities identified. Refracting the light, Introspection looks inward to who one is, what one does, and why one does it.

Categories are never perfect. To be sure, many of the activities cited could come under multiple categories. Yoga could be considered as much Introspection as Health. Attending a complex play could fit under Removal and Intellectual. But for expository purposes, these categories capture responses fairly well.

What can we take from this?

- Sixty-four percent of high level executives were either vaguely, or not at all, aware that there are simple measures they can take to ameliorate the stifling effect of stress in their professional and professional lives. That’s not good news. The word has apparently not gotten out. Responsible organizations should take action to increase employee awareness of this fact.

- Busy executives are busy taking care of business, not themselves. A pitifully high 40% of executives in this study said they engaged in renewal activities once or less a week. The noxious build-up of neuro-chemicals will certainly catch up to them. And 20 to 30 minutes a day is all that’s required. Some firms have recognized that a renewed executive is a better executive, and have built programs to allow valued employees to do so. Still more should.

- The range of reported renewal activities is vast. Physical and mental, active and passive, energizing and relaxing, transporting and fun, there are so many choices to suit ones preferences and lifestyle. Devoting very little time to the available host of these will pay dividends. This study provides a bead on what can we done. Once again, an enlightened firm might circulate a list of possible activities.

Although our organizations could play a more substantial and supportive role, in the final analysis, individuals are responsible for renewing themselves. The sources of renewal are many, but we’ve got to intentionally engage them before the switch flips.

For the Harvard Business Review version, click here.

- Business Leaders must face ultimate Covid Question, and a clash of Interests - January 14, 2022

- “Homers” are Creating the Soulless Downtown - December 27, 2021

- Revising Urban Economies by Returning to the Office: The case of the Nation’s Capital - November 21, 2021

Subscribe to my channel

Subscribe to my channel