The world tends toward continuums. Hot and cold have warm and cool along the way. Big and small have all manner of magnitude in the middle. Even black and white have hues between. Winter, spring, summer, and fall represent varying points along a gradual scale marking this and that. Degrees between something and nothing, more and less, a lot a little. Continuity is the way of things. It is deeply rooted in our thinking.

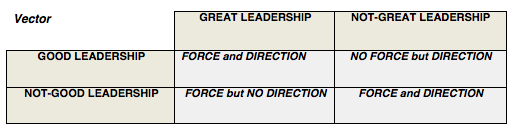

But not all things conform to the form, and leadership is one of those things. Leadership is not one dimensional. It doesn’t run from one end to the other, great to good to bad. The force and direction of leadership–in physics, its vector–is paradoxical. Leadership can be great and good, one but not the other, or neither.

Take the words great and good in turn. Every dictionary definition of “great” begins with being unusually intense or powerful. Either “to great effect” or “great effort” captures the word. Great is a force. True, great also means “very good,” but that is not its primary meaning. As for “good,” dictionary entries always contains morality, virtue, and ethics. “Good person” or “good decision.” Although good can also refer to the quality of something–contrasted against the commonly understood opposite, bad–in this context good refers to the direction in which action is impelled.

That’s starting point. That great and good leadership are different things. And that the force of the former and the direction of the latter represent the leadership vector.

Great leadership is powerful, dominating, often overwhelming. It can sweep people along through sheer force. Great leadership animates, excites, energizes, and stimulates. It’s a rousing call to action, shocking our complacency and inertia into sharp action. It’s one of the most potent pulls in human history, and as such accounts for much of humanity’s progress.

But great leadership also accounts for much of humanity’s suffering. While it ignites collective action and stirs passion, its direction–toward what ends–depends largely on those that wield its great power. Great has no inherent moral compass, and thus its unpredictable potency can just as easily be put toward pugilistic as peaceful purpose. Great leadership is at the root of most evil, and most good.

In contrast, to speak of good leadership is to speak of protecting and advancing widely accepted principles of means and ends. It means doing the “right” thing. There may be legitimate differences in interpretation of what is right and what is wrong, but long-standing ethics and mores and customs of conduct that have allowed individuals and collectives to survive and thrive are remarkably similar across culture and time. Good heeds the best interests and welfare of others.

Good leadership is not so flash as great leadership. When good rules the day, it’s not so noticeable, as things are transpiring, more or less, as they should. Great is dramatic, whereas good is the blended background; a mere backdrop upon which great deeds unfold. This accounts for why the force of great often overshadows the direction of good.

The figure below illustrates the relationship. Great leadership is plotted horizontally, running from GREAT to NOT GREAT, whereas good leadership is plotted vertically, running from GOOD to NOT GOOD.

In Quadrant 1, great and good co-exist. Here, the vector of great force is melded with good direction. The two don’t always peacefully co-exist, but that’s as it should be. The tension between them galvanizes will and commitment, sparks recurring debate about what great and good mean, and gives rise to a critical and creative climate that fuels progress. This is where people want to be. It’s an enviable place in which to reside, as it combines productive and constructive energy. The waters are crisp and clear. The two towers are in balance; the vector is strong and true.

Moving clockwise, Quadrant 2 combines not-great with good. Although all good intentions exist, the will to implement those is lacking. This may be a pleasant enough place to live and work, but it’s bereft of the vitality that’s absolutely required to advance social, personal, societal, or organizations goals. The direction is spot on, but there’s not enough forward motion to leverage. Moral rectitude is all well and good, but if stalled it means little. Inhabitants of this quadrant dwell in a kind of stagnation. Everyone’s happy but nothing gets done.

If Quadrant 2 is stagnant, Quadrant 3 is a cesspool. Both great and good are absent. The lack of force and direction withers the will and erodes the optimism of even the most stout-hearted. There’s no potency or point. There is none of the energy necessary to compel collective movement to an endpoint, and no value can be attached to a non-existent endpoint. This quadrant has no vector whatsoever. Unfortunately, this describes all to many organizations; listless and fetid.

The confluence of great and not-good leadership in Quadrant 4 is frighteningly explosive. It’s a bubbling caldron that could combust at any minute. Herein danger lies. The sweeping force of great has no countervailing direction for good. It’s an environment of excitable, concentrated participation coupled with tenuously defined purpose. The force is mighty but the direction unprincipled. The potential for horrifying destruction thrives in these waters. Without good to hold great at bay, there’s no telling what can be wrought. There is still a vector, a swift and strong one, but its ultimate destination is in serious question.

It’s natural to think of leadership as a continuum, running from great to good. To do so, though, is to be beholden to a mistaken view that they are the same things. That they are variations of the same thing, when in fact they are discrete things. To be sure, separating them seems to be counter-intuitive, but it’s absolutely necessary to understand the very elements that explain leadership’s operation and impact. Great can be destructive; good can be impotent.

The two surely inextricably and inexorably interact, and the product of that interaction illustrates the idea of the leadership vector. There is great–a force that is often unexplainable, often irrational, and, importantly, often ungovernable. Then there is good–a direction that is north-star true, providing the point of purpose of mutual benefit. The former moves, the latter aims.

Great and good are twins and spouses. They can not exist without each other. To attempt to understand leadership without considering their interplay is to miss the elemental nature of our greatest hopes and fears.

For the Harvard Business Review versino, click here https://hbr.org/2016/09/the-difference-between-good-leaders-and-great-ones

- Business Leaders must face ultimate Covid Question, and a clash of Interests - January 14, 2022

- “Homers” are Creating the Soulless Downtown - December 27, 2021

- Revising Urban Economies by Returning to the Office: The case of the Nation’s Capital - November 21, 2021

Subscribe to my channel

Subscribe to my channel

Thanks, Dr. Bailey! I think this idea is so important. If we’re going to take time to develop our leadership abilities, it is so important that we don’t neglect the development of our moral compass. Too many people can be hurt by great leadership up to no good!

Dr. Bailey. An interesting read! Thank you for this piece.